What is an ETF? The Ultimate Guide for Beginners

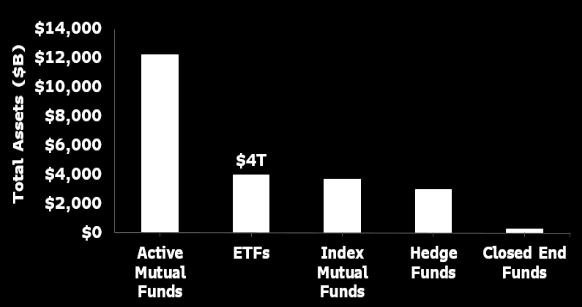

Over the past decade, ETFs have surged in popularity. In the U.S. alone, there are now more than 2,200 ETFs, with combined assets under management of $4 trillion (that’s trillion, with a T). In a 2019 survey by Charles Schwab, 79% of investors said that ETFs were their preferred investment vehicle and 63% responded that they saw ETFs as their primary investment vehicle moving forward. For younger investors, the appetite and interest in ETFs is even more pronounced. A remarkable 90% of millennial respondents, aged 25 to 38, reported ETFs as their investment vehicle of choice.

Source: @mbarna6 on Twitter.

There are several reasons for the secular growth into ETFs - increased transparency, improved liquidity, and lower fees versus alternatives, to name a few - yet the ETF structure remains somewhat misunderstood by retail and institutional investors alike. Here at Roundhill Investments, we’ve gathered information for you and will address some common misconceptions while explaining the ETF structure in detail.

What is an ETF?

ETFs, or exchange-traded funds, are simple but elegant investment vehicles. ETFs trade intraday on exchanges, like stocks. Yet unlike stocks, an investment in an ETF is not an investment in a single company. Investing in an ETF provides diversified exposure to a basket of securities, which can include stocks, bonds, commodities and more.

Most ETFs are passively managed. In passively managed funds, holdings inside the ETF are meant to track a benchmark, or index, of securities. This differs from actively managed funds, where fund portfolio managers are hired to pick which securities to buy and which to sell. The first ETF, which listed in 1993 on the American Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol “SPY”, tracks the S&P 500 Index, a popular index of the largest 500 stocks in the U.S.

How are ETFs Valued?

While ETFs are traded on an exchange, and can theoretically change hands at any price, ETFs typically trade at or around Net Asset Value. Net Asset Value, or “NAV”, is the fancy way of saying - what is one share of the ETF worth? The concept of “worth” is imperfectly defined for an individual stock - some market participants buy or sell stocks because they believe the stock is fundamentally overvalued or undervalued, while other traders look to technical analysis, such as simple moving averages, to make investment decisions. At the end of the day, one method or strategy is neither right nor wrong, and the only “true” value of a stock is the price it last traded for. In the case of an ETF, however, there is a “true” value, called “Net Asset Value”.

Take a simple example of an ETF with $100 million in assets under management (what’s been invested over time into the ETF). The ETF holds $50,000,000 worth of Apple stock and has $50,000,000 worth of USD. What would you pay for the ETF? Putting aside any opinions as to whether Apple’s stock will go higher or lower in the future, the answer is $100,000,000. If there are 1,000,000 shares of the ETF outstanding, each ETF share would then have a Net Asset Value of $100, given the simple calculation of $100,000,000 / 1,000,000 shares = $100 NAV per share.

How do ETFs Work?

Source: Roundhill Investments

Source: Roundhill Investments

Well, what happens when you log onto your brokerage account and place an order to buy shares of an ETF? Let’s break it down, step-by-step.

For this example, let’s suppose you are interested in investing a portion of your portfolio into U.S.-based stocks. Your research leads you to the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSE: SPY), due to its high liquidity and low costs.

Step 1: You place an order with your broker to buy 100 shares of SPY at $300.

If someone else is selling their already-owned shares at a price of $300, the trade is executed and you now own your shares. The trade is complete.

However, there is not always a “natural seller” of SPY shares. In this instance, we move to step 2.

Step 2: A trading firm, commonly referred to as a “market maker” sells you 100 shares of SPY at $300. Market makers are in the business of, well, making markets (i.e. offering to simultaneously buy and sell) stocks and ETFs at different prices.

Unlike the seller in Step 1, the market maker didn’t own any shares of SPY. Instead, the market maker borrows 100 shares of SPY (from someone else who did previously buy them) in order to sell them to you. Following the trade, the market maker is now “short” 100 shares of the ETF.

Step 3: Market makers are not in the business of speculating. They typically make their money from collecting spreads (the difference between a “bid price” and an “ask price”) or by being paid rebates from the exchange. Therefore, the market maker in our example doesn’t want to be short 100 shares of SPY. Why? Because what happens if SPY increases in price by $1? They would stand to lose -100 shares * $1 price increase = -$100.

To counter this risk, the market maker turns around and simultaneously buys shares in all the stocks in the S&P 500, ideally at their exact weightings. The market maker is now long the 500 stocks in S&P 500, and at the same time, short SPY. They are perfectly hedged.

Step 4: SPY continues to trade throughout the day, and from time to time, the market maker repeats this process of shorting SPY and buying the S&P 500 stocks. Eventually, the market maker is short 50,000 shares of SPY, and long 50,000 shares worth (approximately $15 million) of S&P 500 stocks.

Step 5: The market maker (in conjunction with an Authorized Participant, or “AP”) delivers the $15 million worth of stocks to the ETF issuer, who provides them with 50,000 newly created shares of SPY. The market maker is now long 50,000 shares of SPY, in addition to being short 50,000 shares of SPY. Their position is flat.

This is called the creation process. It works in reverse too, when investors are selling the ETF. That is referred to as the redemption process. Creations and redemptions are the primary function that differentiate ETFs from mutual funds - allowing ETFs to trade intraday and, typically, without significant premiums or discounts to the proper Net Asset Value (NAV) of the fund.

Net Asset Value is a fancy way of saying “the value of all of the securities that an ETF holds”. Remember, stocks are valued on the basis on what a buyer is willing to pay. Funds, however, have exact values, based on the trading prices of all the components that make up the fund. While there is no “right” or “wrong” price for a stock to trade at (valuations can seem irrational to one person and rational to another), ETFs have a “right” price - the ETF NAV.

ETFs vs Mutual Funds vs Stocks

Taking this a step further, we analyze the primary differences between ETFs, mutual funds, and individual stocks in the table below.

| ETFs | Mutual | Stocks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diversification | Yes | Yes | No |

| Fees | Yes | Yes | No |

| Liquidity | Intraday | End of Day | Intraday |

| Transparency | Yes | No | Yes |

| Short Selling | Yes | No | Yes |

| Options | Yes | No | Yes |

Potential Benefits of ETFs

As the above chart highlights, ETFs combine some of the best attributes of mutual funds and individual stocks into a single structure.

Diversification

ETFs typically provide diversification, similar to that of mutual funds. By buying shares of a single ETF, investors can gain exposure to a basket of various securities, including stocks, bonds, commodities and futures. ETFs can be useful for investors constructing portfolios and in terms of asset allocation. Imagine buying all 500 stocks in the S&P 500, versus buying one share of SPY.

Low Costs

When buying or selling an ETF, investors are typically charged a commission, like when buying a stock. However, ETFs are continually being offered commission-free through various brokers, including TD Ameritrade, Charles Schwab, and Vanguard. Robinhood offers zero-commission trades on both individual stocks and ETFs. Mutual funds, however, can include additional fees when buying or selling. For example, mutual fund sales loads can be as high as 3.75-5.75% for Class A shares. (This being said, no-load mutual funds can be superior to ETFs from a cost perspective for long-term investors.)

While individual stocks are free to hold once bought, ETFs and mutual funds charge a management fee. For ETFs, these fees are typically low. The average equity index ETF charges an annual management fee of 0.49% per year, or roughly $49 a year per $10,000 invested. Mutual fund fees are generally higher, coming in at an average of 0.62%, per the 2019 ICI Factbook.

In addition to commissions and management fees, mutual funds may charge additional fees, including: 12b-1 fees, redemption fees, exchange fees, account fees, and other expenses.

Liquidity

As mentioned above, ETFs trade intraday on exchanges, like individual stocks. Naturally, this allows for increased liquidity when compared to mutual funds, which only trade once a day. Yet despite their simplicity, the liquidity of ETFs is commonly misunderstood – and underestimated.

While the historical trading volumes for an individual stock is likely a decent proxy for the stock’s liquidity going forward (barring events with increased volumes, like earnings announcements), an ETF’s liquidity is independent of how much it has traded in the past.

Instead, ETF liquidity is determined and calculated based on how liquid its underlying holdings are. This doesn’t mean you should go place a market order to buy $10 million worth of an obscure ETF, but it also doesn’t mean you necessarily shouldn’t. Let’s take an example of a hypothetical ETF tracking the S&P 500, ticker XYZ. XYZ has $5 million in assets in trades an average of 100 shares per day. On the surface, this fund has very little in common with SPY, the most heavily traded ETF in the world. XYZ does, however, hold all the stocks in the S&P 500 in their proportional weights, just like SPY.

Suppose we place a trade to buy $100 million worth of XYZ. If we bought $100 million of a small cap stock, the price would likely go soaring (and investors would rumor monger about which hedge fund took a position). In the case of XYZ, however, the ETF price has the potential to be relatively unaffected. As a result of the creation and redemption process, our $100 million buy order could be absorbed by a market maker, who simultaneously hedges their newly established short XYZ position by buying $100 million worth of S&P 500 stocks. Unless the stocks themselves increased in price, our XYZ order is likely to be filled at or around NAV.

While this concept is foreign to many stock investors – including some of the most sophisticated institutional traders – it is absolutely critical to understanding ETFs. Repeat after me: ETFs are as liquid, or as illiquid, as the securities they hold. Not the other way around.

If you’re interested in learning more about ETF liquidity, I recommend reading Dave Abner’s ETF Handbook, where Dave introduces this concept as “ETF Implied Liquidity”.

Transparency

ETFs have increased transparency when compared to mutual funds. ETFs publish their holdings on their websites at the end of every day, allowing investors to know exactly what securities they hold. Cathie Wood’s ARK Invest even updates investors intraday, emailing trade notifications in real-time.

Mutual funds are only required to release holdings information once a quarter, leaving investors temporarily in the dark.

Tradeability

As mentioned above, ETFs trade intraday like stocks. Mutual funds only trade at the end of each trading day. However, the ability to trade intraday comes with additional complexity. Mutual fund trades will always be executed at NAV – ETF trades, however, can potentially take place at a premium or discount to NAV. While the market-maker arbitrage mechanism tends to keep deviations in line, this means ETF investors need to pay extra close attention to ensure a proper execution.

ETFs also offer additional trading features beyond mutual funds, including the potential for short-selling, and buying and selling options.

Taxes

ETFs, much like individual stocks, leave tax realization decisions to the end investor, meaning ETF and stock investors will typically not pay capital gains taxes (there are certainly exceptions) until their position is sold. This differs from mutual funds, which distribute capital gains to investors from time to time. In these instances, mutual fund investors can be on the hook for paying taxes - even if they have not yet sold their position in the fund.

We address the tax functionality of ETFs in greater detail below.

ETF Fees Explained

As highlighted above, ETFs charge fees to their investors. These fees, which are captured in the fund’s expense ratio are typically represented on an annual basis. If a fund charges a 0.50% expense ratio, the ETF issuer will collect $50 a year per $10,000 invested. While quoted annually, ETF fees are accrued on a daily basis and applied against the ETF’s Net Asset Value. This daily accrual allows for investors on December 31 to pay their fair share of fees when compared to an investor who has held since January 1.

Securities lending revenue, revenue derived from loaning out securities in an ETF portfolio for a fee, can be used to offset ETF investors fees. In some cases, securities lending revenue has managed to fully offset ETF expense ratios, allowing the fund to actually outperform the Index it intended to track.

In 2018, Lara Crigger of ETF.com published a deep dive on securities lending in ETFs.

How are ETFs Taxed?

Investors in ETFs pay capital gains taxes when selling their positions and pay taxes on dividends received, like investors in individual stocks. However, as a result of their unique structure, ETFs receive favorable tax treatment as compared to mutual funds.

ETFs can defer taxes for investors via the in-kind creation and redemption process, a subject that has been covered extensively – both favorably (by our friend, Dave Nadig) and unfavorably. The way this feature works is relatively simple. ETF portfolio managers use redemptions to get rid of low cost-basis holdings, while utilizing creations to refresh with higher cost basis holdings. When investors (APs) want to get out of an ETF, they are provided with low cost holdings in exchange for ETF shares. When investors (APs) want to buy into an ETF, they provide new (i.e. high) cost holdings in exchange for newly created ETF shares. This ongoing process allows for well-managed ETFs to continually defer the realization of gains. As a result, ETF investors only realize capital gains when they decide to sell their own shares of the ETF.

Mutual funds, on the other hand, lack the creation / redemption feature. Therefore, when an investor wants to sell a mutual fund, mutual fund holdings are sold in exchange for cash to be provided to the investor. These transactions can potentially result in the realization of gains for the mutual fund. At the end of the year, the mutual fund then distributes those capital gains to all investors, including those who may have an unrealized loss in the mutual fund itself.

This concept can be tricky to grasp, but high-level concept is what is important: ETFs can continually “refresh” their cost basis in the securities they hold.

This all being said, we are not tax advisors. Consult your tax advisor for any and all tax related questions.

What Types of ETFs are There?

The first important distinction to consider when looking at an ETF investment is whether the fund is passively or actively managed.

Passive ETFs

ETFs that are designed to track a benchmark, or index of securities.

Active ETFs

Actively-managed ETFs are like actively managed mutual funds. Portfolio managers of active ETFs determine which securities to buy and sell. Recently, the SEC approved non-transparent active ETFs.

The second, arguably more important distinction, is that of considering what type of securities a given ETF holds.

Equity ETFs

As the name suggests, these ETFs invest in stocks. Equity ETFs can vary in their mandate significantly, including selecting stocks by geography, by sector, by market cap, by fundamentals, by theme… and more.

Fixed Income ETFs

Similar to Equity ETFs, these funds can target different areas of the fixed income market, and therefore allocate to bonds instead of stocks.

Commodity ETFs

Commodity-based ETFs typically come in two forms – physically backed or futures based. While physically backed commodity ETFs actually buy and hold the relevant commodity, futures-based ETFs typically own front-end futures contracts, introducing additional complexity.

Other ETFs

There are various types of other ETFs including asset allocation ETFs (which sometimes hold other ETFs), alternative ETFs (which seek to replicate hedge-fund-like strategies), volatility ETFs and currency ETFs. Bitcoin ETFs, while not yet approved, have been filed for approval with the SEC.

What is a Leveraged ETF?

Before we address leveraged ETFs, most investors should understand: we believe 99% of you should not be trading or investing in leveraged products.

With that in mind, leveraged ETFs seek to provide enhanced exposure to a given benchmark. Leveraged ETFs utilize leverage in an attempt to 2x, 3x, -2x, -3x, or otherwise amplify the returns of an index. These ETFs are typically designed to rebalance daily, serving as trading vehicles for sophisticated investors. Due to the daily rebalancing feature, these funds can suffer from decay over time.

Thematic ETFs

As discussed above, certain equity ETFs seek to provide exposure to themes. Typically, these themes don’t fall nicely into pre-defined sectors or geographies, but rather attempt to identify companies which are exposed to developing themes in the equity markets.

Thematic ETFs have increased in popularity over the past few years. Popular thematic exposures include: Robotics & Automation, Cybersecurity, Blockchain, Cloud Computing, Cannabis, and Esports.

For example, we launched the Roundhill BITKRAFT Esports Index at the beginning of the year. The Index is designed to track the growing business of electronic sports, or “esports”. Index holdings are diversified in terms of sector, ranging from game developers to gaming hardware companies to game streaming platforms. Index components are diverse from a geographic standpoint as well, with roughly 40% of the weighting in the EU, 40% in Asia and 20% in U.S. companies. While the individual companies may differ from one another, we believe that the collective group provides investors with a way to track the esports industry holistically. We wrote an earlier blog post on how we view thematic investing and why it is important for most investors – you can check it out here.

For investors looking to capture exposures not easily defined by sector classifications, thematic ETFs can provide an easy-to-use tool in the form of a single ETF ticker.

How to Buy an ETF?

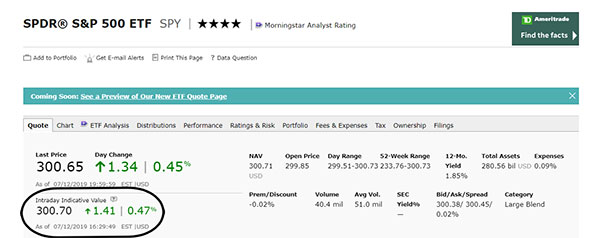

Once you’ve decided on an ETF you’d like to buy (or sell short), be sure to first check the fund’s Intraday Indicative Value – another fancy term that really just means “current NAV”. This can be found on many publicly available sources, including Morningstar – see below.

For highly traded ETFs, this exercise is less critical. For ETFs that are less frequently traded, however, it is important to compare the “current NAV” versus the bid and ask prices. If the ask price is too high, you may want to consider placing a limit order.

As previously discussed, ETF trading can be done through your current brokerage platform, whether online or otherwise. Virtually all U.S. brokerages offer ETF trading just as they would for individual stocks.

Conclusion

ETFs will likely continue to be an important part of the investment landscape. As investors, it is important we educate ourselves and understand the nuances of ETFs and how they differ from investments in individual stocks or mutual funds. This guide is meant to be a starting point for new investors, not a comprehensive guide and certainly not investment advice. For investors looking to do a deep dive, ETF.com offers a wealth of information. Happy trading all and be sure to check us out at Roundhill Investments!