The Rise of Gaming as a Service

What is GaaS?

Games as a service (GaaS) is a relatively new monetization model for the video games industry, taking a page out of the software as a service (SaaS) playbook. GaaS aims to monetize video games through a continuing revenue model, which has increasingly involved a free-to-play launch followed by ongoing microtransactions or downloadable content (DLC). Almost all these games have online multiplayer, allowing users to directly purchase items (microtransactions), or earn them by levelling up via a paid season pass, and to use this newly earned loot in-game.

This model has extended the lifespan of many games and has resulted in publishers employing GaaS to have fewer and fewer releases each year. Revenues have shifted from being concentrated around game launches to recurring throughout the entire year on existing video games. GaaS has also cultivated thriving virtual economies in several games across MMOs, first person shooters, and other genres.

History of Digital Distribution

The odds are that your favorite AAA title today allows you to execute microtransactions in-game, to change the appearance of your character or even get an advantage over other players. Also likely is that your game of choice requires an internet connection to play, which is precisely how microtransactions got started. Before consoles were truly internet-enabled prior to the sixth generation (PS2, Xbox, Gamecube), everything you bought had to come on the disk or cartridge. Rather than have expansions or downloadable content (DLC) like today, publishers would choose to promptly release a sequel if the previous game had enough momentum. They could also release the expansion on another disc, which would then require a complicated sequence of removing the old disc and inserting the new one. This also meant that there were no content patches, and potentially game-breaking bugs couldn’t be hotfixed. In this regard, games were not hugely different from other media like movies or music – what you experienced on launch was what you got forever.

Digital distribution and microtransactions go hand in hand. For years, bandwidth was simply too slow for entire games to be downloaded digitally, and the infrastructure was not yet in place. In 2003, while the PS2 was still in its stride, the average high-end user had a connection speed around 1.5Mbps, and DVDs could hold up to 4.7GB of storage. Assuming a wired connection and 100% bandwidth utilization, it would take between 7 and 8 hours to download a single title. Furthermore, the PS2’s hard drive could hold up to 40GB with limited expansion capabilities, meaning that you could only have around eight games before having to uninstall and make space.

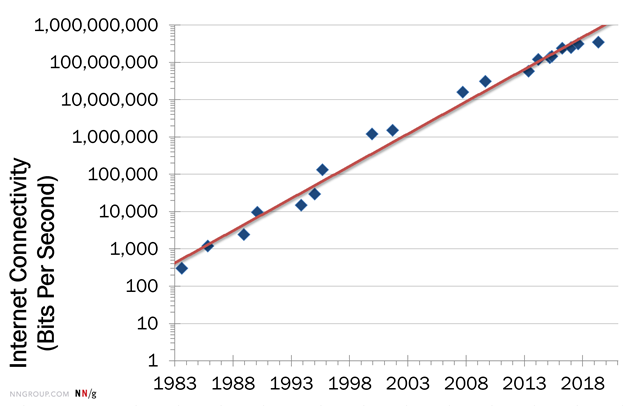

Luckily for the industry, technology advances exponentially. Nielsen’s Law of Internet Bandwidth shows that connectivity speed has been growing at a 50% CAGR for the last 35 years, with an R2 of 0.99. This means that speed increases roughly 57x every 10 years, illustrated by Figure 1 below, which is on a logarithmic scale. For reference, one million bits per second equal 1Mbps. Coupled with rapidly growing hard drive capacity and decreasing costs, the stage was set for digital (or discless) distribution in the last half of the 2000s.

Figure 1: Bandwidth speeds from 1983 through today

Source: Nielsen Norman Group, as of Sep 2019.

The Beginning of Microtransactions

The first microtransaction sold by a major publisher was by Bethesda, for The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion in 2006. For $2.50 on Xbox or $1.99 on PC, you could purchase a set of armor for your horse – the first set was free, and future sets cost the player in-game gold. After release, the DLC was widely parodied by gaming blogs like Joystiq, and Bethesda was criticized for charging real money for an in-game item. However, the experiment still proved successful for the publisher, and new, small content updates were released throughout 2006 and 2007 at lower prices with better reception. Two more substantial expansion packs also followed – Knights of the Nine in 2006 for $10, and Shivering Isles in 2007 for $30. These were both available via digital download and physical disc.

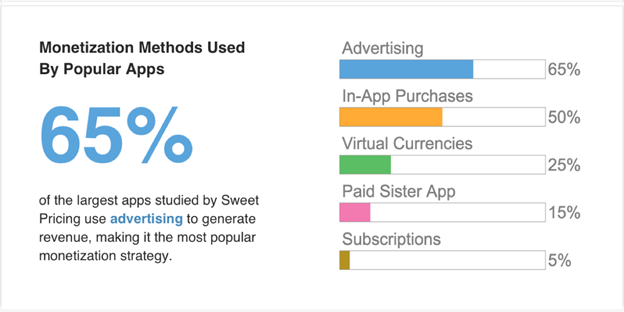

From there, publishers slowly continued to include microtransactions and expansions as part of their monetization model. When the iOS store launched in 2008, microtransactions grew rapidly as the freemium model rose to prominence. These types of transactions were dubbed “in-app purchases” by Apple. Many games and applications were launched for no upfront cost but used microtransactions to generate significant revenues for publishers. Additionally, many of these apps also feature advertisements, which are sometimes able to be removed via a one-time fee or a recurring subscription. The goal here is to get the product in the hands of as many consumers as possible, who will then either be monetized via ads, in-app purchases, or both. This model, which naturally results in more downloads than paid counterparts, sends apps to the top of the App Store charts, resulting in virality and even more momentum.

Figure 2: Most common monetization models for popular apps

Source: Sweet Pricing, as of January 2017.

The Team Fortress 2 Experiment

Until 2010, in-game transactions would sporadically appear in console and PC games but were not yet a core part of the ecosystem. This all changed in September of that year when Valve introduced the Mann-Conomy Update for Team Fortress 2. For context, TF2 was originally released in 2007 for both PC and consoles as part of the game bundle, The Orange Box. The game was particularly a hit on PC, which was home to Valve’s key audience, and became one of the most popular titles on Steam. In the game, you can select from nine classes, each with their own unique item loadout. As time went on, more and more items became available for each class, both in the form of weapons and hat-based cosmetics. By 2010 there were hundreds of items in total, including promotional items from other Valve games like Left 4 Dead.

The Mann-Conomy Update introduced 65 new items into the game, including a host of community created content. Creators received a percentage of revenues, incentivizing them to create quality cosmetics, and shoring up Valve’s resources. More importantly, it introduced the Mann Co. Store, an in-game microtransaction shop where players could directly purchase cosmetics and weapons. Players could also purchase keys, which would open crates that randomly dropped during matches. These crates had a loot pool which included a 1% chance of an “unusual” cosmetic hat, which would cause the item to emanate an effect visible to everyone in the game. This was one of the first instances of paid loot crates with random drops, and hundreds of games would follow suit.

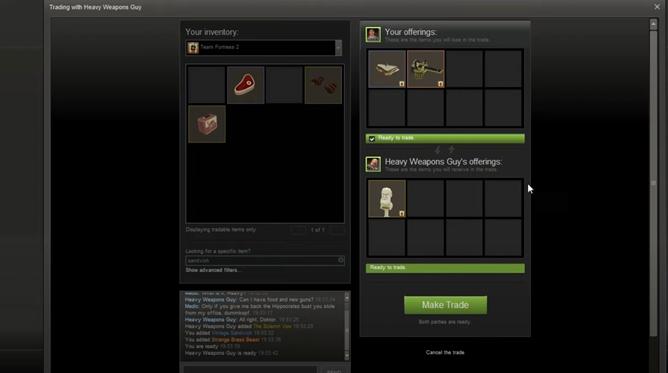

The update also brought with it trading – an in-game system where players could swap most items with each other. At first, trading was limited to players on the same server, and on each other’s friends list. In August 2011, Steam trading was introduced – trades could now be executed in the Steam client, and players could trade items from other games, or even games themselves. Around this time, TF2 became free-to-play as well, opening the floodgates for this burgeoning market.

Figure 3: Team Fortress 2 trading window example

In-game screenshot of the TF2 in-game trading window

Websites formed left and right to facilitate a trading marketplace, where traders could search for the items they wanted among listings from other traders. Forums were created for the sole purpose of TF2 trading, with different boards for different classes of items. Unusuals commanded the highest prices, depending on the specific hat and effect, followed by rare hats and cosmetics. While item-to-item trading was possible, most sophisticated trades were priced in terms of keys, or for large trades, cosmetic items called “earbuds”. With enough trust, transactions were also done using Paypal or Bitcoin, though this required one player sending their items first.

While keys were purchasable for $2.50 directly from Valve, the secondary market for them around 2012 priced them between $1.25 and $1.50. Earbuds were a unique cosmetic item that were given to players who launched TF2 using macOS between June 10th and August 16th, 2010. After this event, there were a fixed number in circulation, allowing a value to be ascribed to them. In 2012, when the market started to take off, earbuds were worth between $30 and $35, though the price could be volatile intraday. I used to mainly make markets for earbuds with about a $3 spread, and knew many traders employing a similar strategy. The community was tight knit, and top traders with enough reputation could transact in cash with relative ease. Many opted to use Bitcoin, to circumvent Paypal’s transaction costs and policy which technically forbade trading digital goods.

Future Greek finance minister Yiannis Varoufakis was hired by Valve in March 2012 as a consultant to research the rapidly growing virtual economy Valve had created. Among other topics, he studied arbitrage in the TF2 market, and how imbalances could remain for a prolonged period of time. His purview soon after included Valve’s rapidly growing MOBA Dota 2, which would eventually become one of the most popular esports in the world with massive tournament prize pools. Headlines swirled around such a high-profile hire in an industry still unknown to the masses, and dozens of publishers seized the opportunity to monetize existing IP with a similar model. Eventually, Valve introduced a Steam Community Marketplace, where people could list their items directly through Steam, and Valve would take a portion of revenue. Any game on Steam with microtransactions now has their own listings on this store.

Figure 4: Top online games in 2013 by free-to-play earnings

Source: SuperData Research, as of 2013.

Evolving Revenue Model

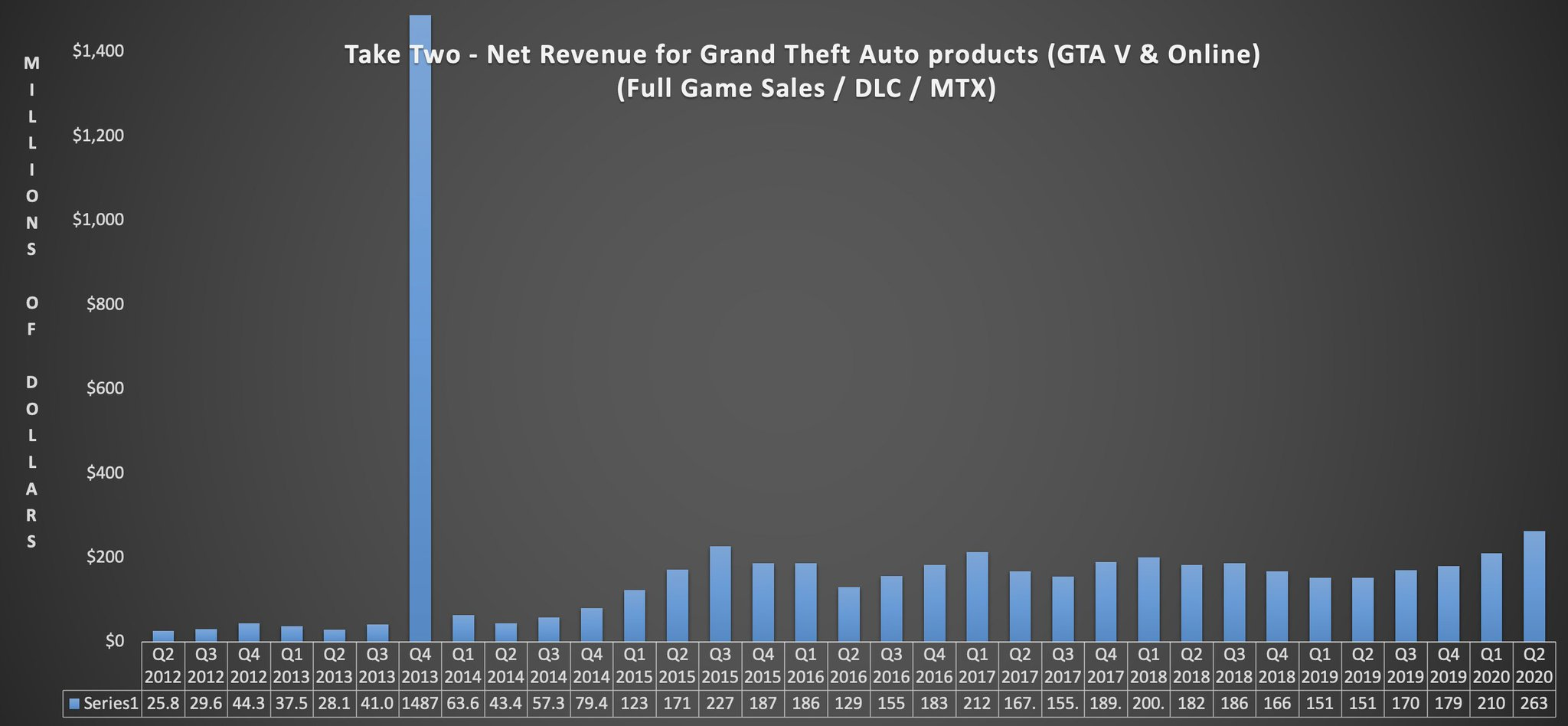

Like TF2, the top titles today derive substantial revenue from in-game transactions. Games from AAA publishers are released sporadically, with most resources devoted to supporting the games post-launch. For example, Grand Theft Auto V (and Grand Theft Auto Online) was released in 2013 for the PS3 and Xbox 360, and still sees constant updates from Rockstar Games, a subsidiary of Take-Two Interactive. For one, the game was brought to PS4 and Xbox One in 2014 and is scheduled to come to the PS5 and Xbox Series X in late 2021. This means that at a minimum, the title will have eight years of support, far longer than any other GTA installment. It will also mark the longest gap between releases for Rockstar North in its 32-year history.

In 2019, more than half a decade after the game’s launch, GTAV is still one of the top earning titles globally. The game grossed $595 million, largely made up of transactions for GTA dollars, which can also be earned in-game and are used to purchase homes, cars, and businesses for the player character. FIFA 19 and Modern Warfare both grossed more, but were also launched in 2019 and earned some revenue from their $60 purchase price. Rockstar continues to actively run promotions for GTAV and maintains a strong presence for the game across social media. As recently as July 2019, a casino launched in GTA Online, which allows you to trade GTA cash for casino chips, which you can then use to gamble on various games inside. Aside from the revenue spike around the initial launch, all future quarters since Q4 2013 (except for Q2 2014) have seen significant revenue growth.

Figure 5: Take Two Interactive net revenue for GTA V & Online

Source: Daniel Ahmad on Twitter, Take-Two Interactive - Q2 2020 financial results.

Many other top-grossing games go a step further, and charge for an optional “season pass.” This system provides additional content based on a tiered system, usually tied to the player levelling up and unlocking rewards. The model originated with Dota 2 in 2013 but was popularized by Epic Games’ Fortnite Battle Royale in 2018. Each season, lasting 10 weeks, has its own pass,which costs about $10, and incentivizes gamers to play frequently and unlock all the tiers. There are also unique cosmetic items outside of the season pass that can be purchased directly with V-Bucks, or Fortnite’s premium currency which in turn can be bought with cash. The game itself is free-to-play, but still grossed about $1.8bn in 2019 according to Nielsen, or more than twice as much as the number one premium (paid) game in Figure 6, FIFA 19.

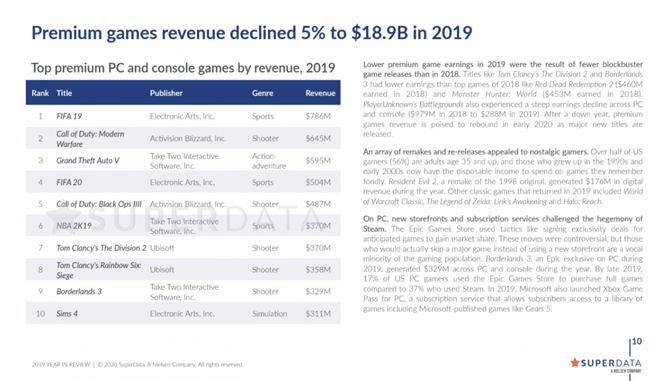

Figure 6: Premium games revenue across PC and console in 2019

Source: SuperData Research, as of January 2020

Another free-to-play example is Bungie’s 2017 title Destiny 2, which is playable on Xbox One, PS4, and PC. The game features three avenues of monetization:

- In-game premium store called Eververse. Transactions are done with the premium currency “silver” which can only be purchased with cash. Most items cost between 500 and 1,000 silver, and 100 silver = $1.

- A seasonal 90-day pass, with 100 tiers based on the player’s level. Currently the pass costs $10.

- Annual expansions, which add a significant amount of content to the base game. These typically range from $25 to $35.

Assuming a gamer buys all four season passes in the year, and purchases a $30 annual expansion, Bungie is netting $70, or $10 more than the typical cost for a premium title upfront. This excludes a small fraction of consumers known as “whales,” who spend significantly on microtransactions and may buy every new release in the store. The more that gamers play to level up their season pass to the maximum level, the more likely it is that they become hooked on Destiny and buy the annual expansions and potentially silver. Bungie has pledged to keep Destiny 2 updated through at least 2022 and have explicitly stated that they prefer this service model over launching a sequel.

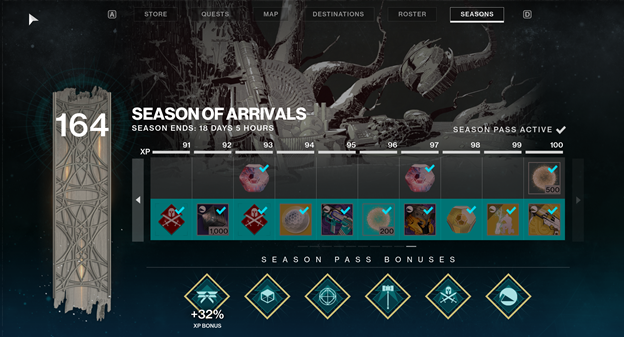

Figure 7: Example of a season pass from Destiny 2

In-game screenshot of Destiny 2’s latest season pass. I am shamelessly 64 levels above the highest tier.

Financial Results of GaaS

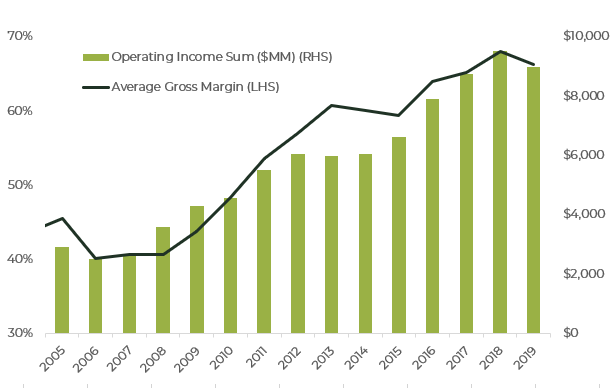

While Bungie is a privately traded company, public publishers like EA, Take-Two Interactive (TTWO), Activision Blizzard (ATVI), and Ubisoft (UBI FP) all employ this model, much to the benefit of shareholders. The graph below takes the simple average of gross margin since 2005 for these three stocks, and overlays it with gross profit growth. This has resulted in rapid price appreciation for gaming stocks, as these twin engines have provided for higher valuations and higher sustained earnings growth. The dark green line plots the average gross margin for these four companies since 2005, showing a clear inflection point near the last half of the 2000s. The lighter bars show the sum of gross profit (revenue - COGS) for ATVI, TTWO, and EA, excluding UBI which only has this breakout going back to 2009. In both cases, the story is clear - gaming is rapidly growing.

Figure 8: Growth of operating income and gross margins for gaming stocks

Source: Roundhill Investments, Bloomberg, as of FY 2019.

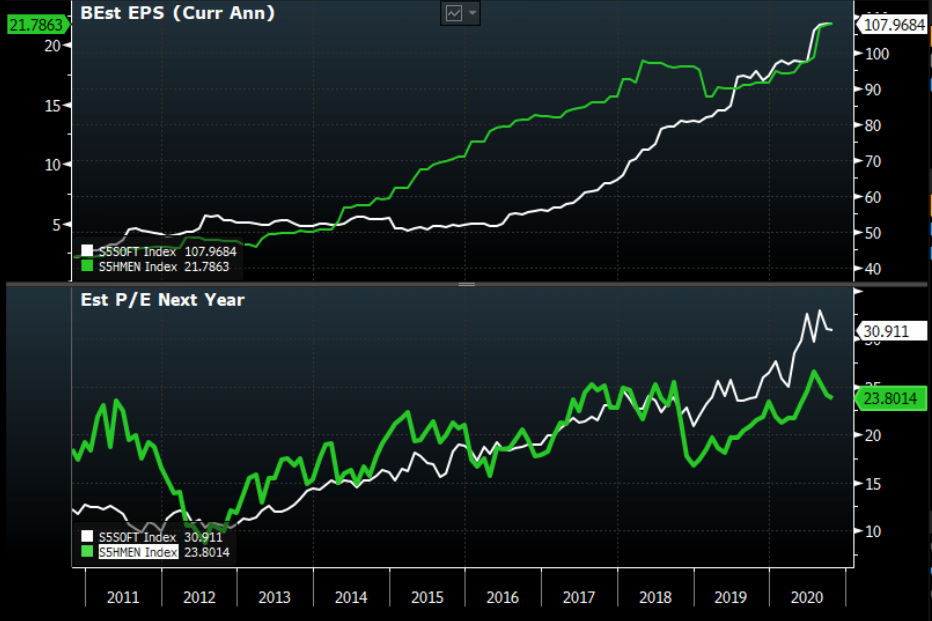

Despite this growth and the similarities of the models, gaming is still behind SaaS from a valuation perspective. The green line in Figure 9 represents the S&P 500 Interactive Home Entertainment Index, which comprises three gaming stocks - TTWO, EA, and ATVI. The white line is the S&P 500 Software Industry Index, containing the fifteen software constituents of the S&P 500. Both are capitalization-weighted, and the data has weekly periodicity over the last ten years ending 10/23/20. On top is an illustration of the indices’ forward looking EPS, which when normalized for both, ended the period nearly on top of each other. Below that is the forward P/E for the indexes, which has shown a clear lag for gaming since 2018. As of 10/23, this gap is about 7 points wide, despite similar earnings growth.

Figure 9: Historical EPS and P/E ratios for software vs gaming indices

Source: Bloomberg, as of 10/23/20.

Wrapping Things Up

Faster internet speeds, larger hard drive capacity, and general improvements in technology have all combined to usher in a new era of service-based gaming. For AAA publishers, games have now become constantly evolving media, and one title can be supported for a decade or more. Free-to-play games with microtransactions and season passes are increasingly becoming the norm, and mobile gaming is starting to converge with console gaming. Revenues have become less concentrated around launches and more supported by recurring services, enticing investors and supporting higher valuations. However, GaaS names still lack the recognition of their SaaS peers, which have also seen more inflows despite similar growth stories.

Going forward, investors should perceive gaming as a subsector of software, rather than as a completely distinct category. The performance of gaming companies over the last couple years has been excellent, extending before the COVID work-from-home environment. With stretched valuations for broad beta and the current low interest rate regime, gaming stocks and funds focused on the sector seem to be well positioned for future growth.

The Roundhill team discusses Gaming As A Service in the video above.